Japan's Populist Revolt, Explained

The world's third largest economy is no longer an exception to the populist wave.

A Familiar Story

Picture the scene; as the economy flounders, and concern over migration fuels ever more fractious social tensions, a surge in support for a right wing populist shatters the political orthodoxy, forever changing the nations political landscape.

It’s a story that will feel very familiar to you, right?

In fact, don’t answer that, I’m going to confidently (arrogantly?) assert that it does indeed sound familiar.

The reason for this confidence is twofold.

Firstly, because yes, this could describe any developed country in 2025, but also because I cheated. According to Substack analytics, not one single reader of Iwakura magazine comes from a country where this does not apply.

The magic of data analysis in action, folks.

But until really quite recently, Japan might have been one of the only contenders considered exempt from this rule. As Trump and Brexit rocked the anglosphere, and as Le Pen, Weidl and Meloni stormed continental Europe, Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) remained calm, steady, and in control as ever.

Alas, no longer.

The Road to the Kantei

The LDP kicked off its leadership contest on Monday, looking to replace outgoing Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, who resigned earlier in September.

The launch of the leadership contest was almost immediately followed by a surge in support for the conservative firebrand who would be Japan’s first female Prime Minister - Sanae Takaichi.

Whilst her main challenger, young centrist Shinjiro Koizumi, had gone into the contest neck and neck with Takaichi, he was immediately beset by scandal, with members of his staff found to be posting false comments of support online, seeing his support plummet.

The scandal soon claimed the head of Koizumi’s PR team, Karen Makishima, who resigned soon after.

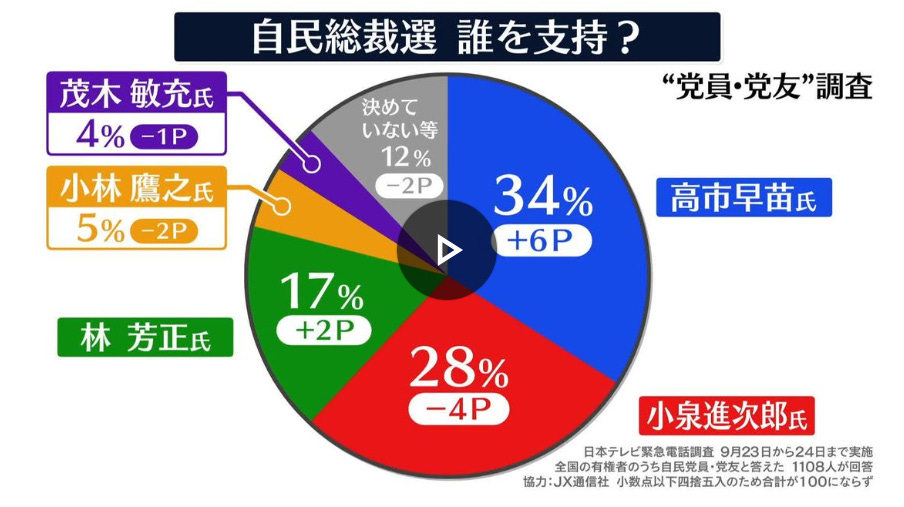

Takaichi now sits 6 points clear of Koizumi, according to an NTV poll of registered LDP members on the 23-24 September, and looks set to increase her lead going forwards.

Whilst Takaichi’s path to the Kantei (the residence of Japan’s Prime Minister - 総理大臣官邸, Sōri Daijin Kantei) may still hold several twists and turns yet, its hard to ignore her decisive lead ahead of the vote on 4 October.

Its even harder to ignore the surge in popularity for her right wing, anti-migration policies, which she has placed front and center of her campaign.

Japan, to cut a long story short, is in the mood for populism.

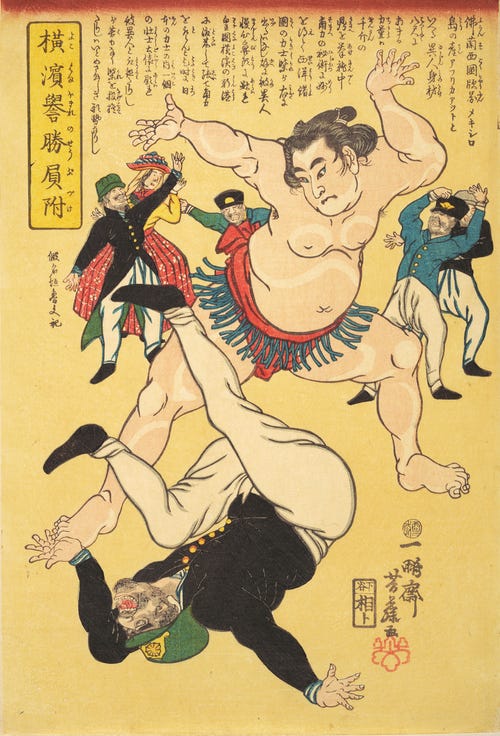

Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians

Japan is no stranger to anti-migrant revolts.

Sonnō jōi (尊王攘夷 - Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians) was the rallying cry of Japan’s modernization movement in the Bakumatsu period (the final fifteen or so years that immediately preceded the end of the Shogunate in 1868).

The jōi (Expel the Barbarians) part of Sonnō jōi provides an apt framing for Japan’s modern political woes.

Japan has seen an explosion in anti-migration sentiment. More than a few Japanese calling for jōi.

In March 2025, a demonstration in Osaka, against Japan’s rapidly growing Kurdish community achieved international fame when Elon Musk tweeted his support.

In that protest, several thousand demonstrators carried banners bearing slogans such as ‘end mass immigration’. Other protests have seen banners such as ‘Kurds should get out of Japan’.

I’m sure it’s catchier in Japanese, but you get the point.

This might be surprise Westerners who have visited Japan. One of the most obvious contrasts between Atlantic nations and Japan is its relative homogeneity - with the most visible foreign presence being Chinese and Vietnamese tourists.

Even then, outside of the heavily trafficked tourist areas of Tokyo (Shibuya Square) or Kyoto, visibly foreign people are relatively few.

This changes somewhat after dark. I am quite partial to taking (jetlag induced) late night/early morning walks when I visit Tokyo, when the cities African and Indian population emerges to staff the plentitude of 7-Elevens, Lawsons, and other flavors of Konbini.

But even accounting for the night economy, the number of foreigners in Japan is staggeringly small.

Japan in its entirely has around 3.8 million foreign born residents in a population of around 120 million. To put that in context, Los Angeles alone has roughly the same number of foreign born residents, and London hosts 5.2 million foreign-born residents.

Viewed from the eyes of an Atlantic nation, one wonders what all the fuss is about.

Migration Frustration

Despite the relative small amount of migrants, Japan has reacted strongly to the steady liberalization of immigration policy.

That liberalization, by the way, is an entirely new thing - having taken place only in the last few years.

Whilst Japan has always had limited visa schemes, but these have always been extremely restrictive and non-permanent in most cases.

An example that I simply cant resist including is the Nikkeijin (Japan’s foreign diaspora) visa scheme, targeting Brazil’s roughly two million citizens of Japanese descent. Two million! Brazil!

But it was only in 2019 that Shinzo Abe oversaw Japan’s first flirtation with migration, introducing the Specified Skilled Worker scheme, liberalizing visa issuance across fourteen key sectors.

It proved to be the crest of the slippery slope, and Prime Ministers Kishida and Ishiba oversaw a spike in expansions to further sectors, allowances and exceptions.

The backlash was immediate and fierce, prompting demonstrations across the country of varying sizes.

We Dont Want to Be Europe

One feature of Japan’s migration protests has been the constant highlighting of Europe as a path that Japan should not follow.

Fears that Japan would undergo the same type of demographic shift and social tensions that define Europe in 2025 are immediately apparent in every aspect of Japan’s migration protests.

A report by libertarian party Nippon Ishin No Kai, for example, warned that Japan would go past the point of no return if it reached the ‘European threshold’ of 10%. Senior officials of the Japanese conservative party, Nippon Hoshuto, explicitly warned against following Europe’s path.

But nor was the issue relegated only to politicians. Academics and journalists also emphasized the need to ‘learn from Europe’s mistakes’ on integration policy.

Economic Troubles

But yet, for all the anger, introducing migration was intended to be the medicine for the comatose Japanese economy.

In 1995, Japan represented 15% of world GDP, but only achieved an average growth rate of 0.7% in the thirty years since, compared to the ~2% achieved by Europe and 2.5% achieved by the United States.

The difference between those rates might feel miniscule, but make no mistake - it’s gargantuan. With the sheer numbers that we talk about when we talk about a modern, developed economy, and the effects of compounding, a 0.5% difference in growth rate has enormous consequences.

For example, an economy with a growth rate of 2.5% - such as the United States, will double in size every 28 years, whereas one with 0.5% will double every 140 years.

And thus, whilst the United States and Europe have seen their economies more or less double since 1995, when mass migration really took off, Japan’s economy has grown so slowly that its relative share of the world market has decreased.

Japan may not want to be Europe in its demographics, but it certainly wants to be more like Europe in its economy.

And herein lies the tension. For all of its flat growth, Japan has held up surprisingly well.

Thirty years without growth has not been the doomsday scenario that many predicted.

The ‘GDP line’ has not gone up, but Japanese standards of living have remained stable. Consumer prices have barely risen at all since the 1990s, and unemployment is low. Japan boasts the highest life expectancy in the world, and few argue that Tokyo is a less pleasant place to live than London.

Japan might have accepted the need for more migration, as the United Kingdom did in the 1970s, or as France and Germany did in the 1960s, had there been an urgent need to reform.

But for many Japanese, the medicine is worse than the disease.

Sanseito - Do It Yourself!

From the rejection of this medicine, Sanseito was born.

Sanseito was born in 2020 as an ultraconservative, right wing populist movement. Founded by Sohei Kamiya, a former LDP politician that Shinzo Abe had personally campaigned for, and a motley crew of YouTube stars, its success was immediate.

In less than five years, the party expanded rapidly and captured 14 seats in the 2025 House of Councilors (upper house) elections, becoming the third largest opposition party behind Japan’s center left and libertarian parties.

The speed of Sanseito’s growth is that, amongst right wing populist parties worldwide, only Italy’s Movimento Cinque Stelle (M5S) has grown faster.

The lesson has not been lost on Japanese politics or politicians - few of whom wish to see a US/Europe style polarization occur.

But neither can Sanseito’s support, or its supporters, be ignored.

Back to Takaichi

Its clear that Sanseito, and the forces driving them, are here to stay.

And as long as they remain, each leap forward and each victory in the story of their spectacular rise will drag the mainstream further to the right. Just as Le Pen reshaped France, and Meloni reshaped Italy.

Japan now faces a choice that will feel familiar to Europeans.

In Takaichi, it has a Meloni-like figure: a limited embrace of the populist revolt, channeled and managed through the establishment. In Koizumi, the choice is a Macron-like centrist who insists the true crisis is economic stagnation, not migration.

On October 4, the LDP will have to decide.

For decades, Japan seemed immune to the populist uprisings that convulsed the West. That immunity has expired. The world’s third-largest economy is about to choose its path — and the choice looks far more familiar than outsiders once believed.