Railguns, Frigates, and Fighters; Japan’s Defence Industry Arrives in Force

Japan’s defence sector is back, and ready to conquer the world. With railguns.

(Rail)Gunning for Glory

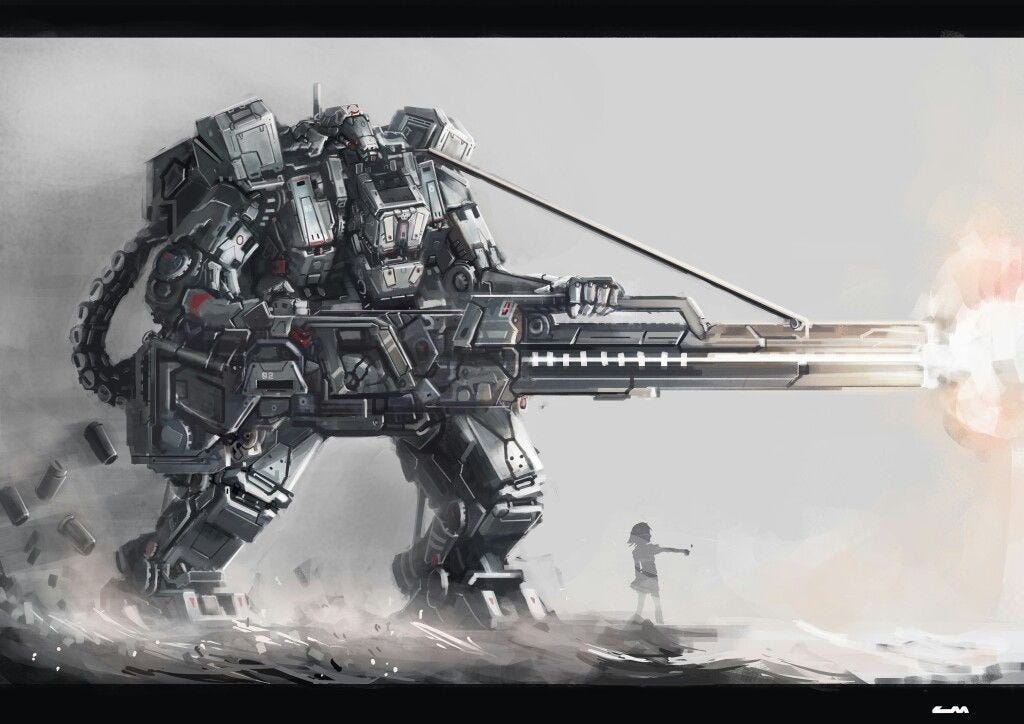

Railguns are, without a doubt, one of the coolest things on planet Earth.

And if, like me, your inner teenager remains a strong influence on your life, I hope that you are now irresistibly hooked on this article, and all the railgun-ny goodness that it contains.

Indeed, that inner teenager has now labelled the Japanese Maritime Self Defence Forces (JMSDF) as ‘officially’ the coolest navy in the world.

This is as its technicians managed to overcome a set of huge engineering problems, to become the worlds most likely candidate to possess a viable, railgun-toting navy.

At least, that’s according to Japan’s Ministry of Defence, who announced that the JS Asuka had successfully carried out a railgun strike upon a sea-based target, over the summer.

Japan, a nation committed to pacifism by its constitution, that also renounces the usage of military force to settle disputes between nations, was perhaps an unlikely candidate to emerge as a world leader in railgun technology.

That is especially so, as the United States itself was forced to end its own development programme in 2021, being unable to render its experiments accurate over long distances, or to solve the problem of its prototypes degrading quickly.

Given that Japan has succeeded where the United States could not, the mission of the JS Asuka becomes reflective of the bigger picture. In a region of the world defined by security threats from Russia, China and North Korea; the Japanese Navy is back (baby!).

Japan’s Quiet Rise to Naval Dominance

Underpinning the success of the JMSDF, as ever, are the legions of private sector companies manufacturing its equipment. These Japanese firms are becoming integral to global security.

In August, for example, Australia announced that it would purchase eleven of Japan’s Mogami-class vessels, at a cost of $6.5bn, soundly beating Germany’s MEKO A-200.

This deal is the largest defence export in Japanese history - and there’s so much more where that came from.

The Mogami class, in service with the JMSDF since 2022, boasts advanced stealth and radar technology, mine laying and detection capabilities, and a relies on automation to enable smaller crew sizes.

It’s newest models, eleven of which will be provided to Australia, and twelve of which will safeguard Japan’s shores, has a true claim to being amongst the best in the world.

Few could have envisaged that the JMSDF, which in 2008 represented the small, regional-at-best force of a pacifist nation, would rise to having best-in-class ships by 2025.

But forget about best-in-class ships, Japan now has a claim to a best-in-class navy. Having increased its numbers by over 50% since the 2008, and with a $350bn five-year defence plan in place since 2022, Japan’s surface fleet outclasses it’s European equivalents (although Europe still retains several strategic assets, such as carriers and nuclear submarines, where Japan falls short).

Abe’s Vision

The man responsible more than any other for this transformation, and the re-emergence of Japan’s naval might, is Shinzo Abe.

One of Japan’s most impactful Prime Ministers, Abe’s reforms in the 2010s allowed Japan’s defence forces, and its defence industry, to thrive.

Whilst these reforms were extensive, it was his reinterpretation of Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution that truly mattered, allowing Japan to practice collective self defence.

And with a docrtine of collective defence, the lifting of certain restrictions on defence exports naturally followed. Allowing exports has proven to be the game changer, in a world where defence companies rely on non-domestic contracts for resources, cash flow, and expertise.

Prior to Abe’s reforms, Japan’s defence sector operated with a purely domestic focus, owing to Japan’s history than any real desire

Without going too far down the historical rabbithole, the Allied occupation of Japan following the Second World War saw a Constitution imposed upon it, including Article 9, forbidding Japan from rearming and rejecting the usage of warfare in disputes between states.

But the world of 1947, when the Constitution was adopted, was not to last long. Two years later, the Chinese Civil War would conclude with a communist victory, and in 1950 the Korean War would break out.

By 1954, the structure of Japan’s Self Defence Forces would emerge, but both it and Japans once mighty defence sector would remain restricted by the constitution until Mr. Abe’s reforms.

A Rising Sun

Mr. Abe’s reforms reflected a broader trend in Japanese society - the realisation that pacifism is no longer sustainable.

We have previously looked at Sanae Takaichi, a strong contender for the next Japanese Prime Minister, and her involvement with the conservative pressure group Nippon Kaigi.

It should be no surprise to anyone that Mr. Abe was also a member of Nippon Kaigi, whos arguments for rearmament and the strengthening of Japan’s military now enjoy widespread reach in Japan’s political right.

Remember, Japan considers Russia to illegally occupy the southernmost four of the Kuril islands - Etorofu, Kunashiri, Shikotan, and Habomai. Between illegal occupation, and an increasingly hostile geopolitical environment, there’s only one conclusion to reach:

Japanese rearmament is here to stay.

And that political stability is very good for business.

It’s difficult for a for-profit company to dedicate the necessary resources to R&D and production to equip a military in peacetime. One of the ways that modern defence companies increase their resources is by actively seeking exports and overseas contracts.

The solidification of Japan’s political case for rearmament has led to a boom, as companies like Mitsui, Kawasaki, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, and Mitsubishi Electric, were suddenly able to expand their domestic defence industries abroad.

Japan’s first major export of defence equipment followed almost immediately (in business terms), with Mitsubishi Electric successfully exporting radar to the Philippines, having won a contract in 2020, and having supplied the equipment since 2023.

In the air too, Japan is ascendent. Mitsubishi Electric again, together with Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, IHI Corporation, and others, form the Japanese side of an Anglo-Italo-Japanese consortium to work on the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP).

GCAP will produce a sixth generation fighter for delivery in the 2030s, and looks set to only truly be rivalled by the United States Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) programme. Further entrenching Japanese expertise, presence and credibility in the defence sector, Japan has done very well out of its participation in this programme.

All this to say, the future is looking bright for the Japanese defence industry. It’s enjoying an economic surge, it’s enjoying strong political backing, and it’s making historic breakthroughs in technology.

The European Connection

Japan’s booming defence industry coincides with similar trends in Europe, which itself is looking to rearm its militaries and expand its own defence industrial base.

Most recently, NATO nations agreed to increase defence spending to 5% of members GDP. This, in effect, will increase European defence spending from 325bn EUR to 900bn EUR.

This pot of money is attracting Japanese business. Beyond the joint consortium created by the GCAP project, Japan appointed a dedicated ambassador to NATO in early 2025, whose remit includes helping Japanese companies access NATO tenders.

The interests of both partners are converging: European financial weight and Japanese technical know-how are a natural match. This partnership is the one to watch.

To put it bluntly; Japan is back.

It’s defence sector can no longer be ignored. From railguns to next-gen fighters, Japan is now a first-tier defence innovator. Europe’s challenge is no longer whether to work with Japan, but how fast.